The Korean Problem and Integration Processes in Northeast Asia

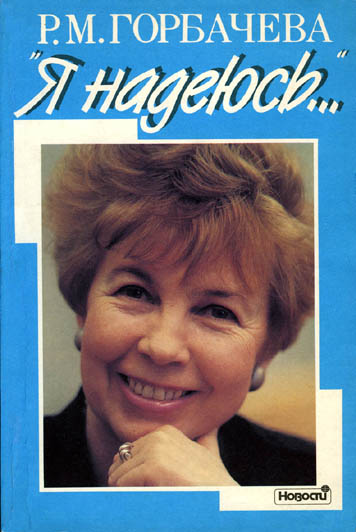

Foreword by Mikhail S. Gorbachev

The Gorbachev Foundation pays great attention to the issues of globalization in all their aspects, including regional.

Globalization is creating opportunities for more efficient utilization of material and spiritual resources, while also creating new problems, of which we have become increasingly aware in the 21st century.

The above is also true of Northeast Asia. This region has many unique features, both inherited from the past and related to the vast differ-ences between the states constituting it. Here, we see the last relic of the Cold War – the rift in the very heart of NEA, in the Korean Peninsula; here, the interests of four great powers – the United States, Russia, China, and Japan – intersect and, in certain ways, clash.

Of course, the situation in the Korean Peninsula and in the subre-gion is now completely different from what it was 15-20 years ago. The stand-off between the two Korean states is no longer a part of the con-frontation between the two superpowers. Russia and China are develop-ing normal relations with both Korean states, which have became mem-bers of the United Nations and are engaged in a dialogue with one another. Japan and the United States have some contacts with DPRK. All this is conducive to the integration processes in the Region. Nevertheless, the main obstacles to their intensification have not been removed and at times get even more complex.

Cooperation between NEA countries still largely depends on the situation in the Korean Peninsula, on the settlement of the North Korean nuclear weapons problem and the relationship between the Republic of Korea and DPRK. Yet it is equally important that any positive develop-ments in the integration processes in the Region facilitate normalization in the Peninsula and bring closer the prospect of the solution of the na-tional problem of the Korean people.

The present Report, prepared at our Foundation with support from the Korea Foundation, deals with all the above issues. Its authors include scholars from the Foundation, the research institutes of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Diplomatic Academy and the Institute of Inter-national Relations of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

I hope this study will contribute to the understanding of the highly complex problems of Northeast Asia, which are of great importance to the international community.

Mikhail Gorbachev

I. Northeast Asia as a Unique Subregion

Northeast Asia (NEA) is a part of the Asian Pacific Region pre-dicted to have a great future role to play in the development of human-kind. This subregion includes six states: South and North Korea, China, Japan, and Russia, and also Mongolia, China being directly represented by its Northeastern Region, and Russia by the Far Eastern Region. These are the countries that are diverse in terms of history, economy and cul-ture. They differ in the lifestyles of their respective populations, eth-nopsychological characteristics, social and economic potential, and the nature of political regimes. The trends in the development of NEA coun-tries in recent decades have been characterized by these countries’ grow-ing diversity and differentiation.

Nevertheless, one can talk about Northeast Asia as not only a geo-graphical notion but as a major subregion with its own geopolitical, geoeconomic and other specific features, which, taken together, enable it to occupy a unique position of its own in the international community.

NEA countries (with the exception of Mongolia) are located along the Pacific Rim and, directly or indirectly, are contiguous territorially. The bulk of their population, except for Russia, belongs to the same race and to one or two similar religions. Their history, with wars, invasions, conquests, domination and subordination of one people to another and movements of large masses of people across ethnic boundaries, has inter-twined the destinies of the peoples of Northeast Asia in many ways. This is bound to be reflected in the current situation and in the way of life of the population of NEA.

World War Two and its consequences came as a shock to all these countries, changing the socio-political structures of the Region’s coun-tries and their position and role in this part of the world and in the global balance of power.

The Soviet Union had a major impact on the course of develop-ments in the Region and in each of its countries, including the division of the Korean Peninsula. First it became a superpower, one of the two poles in a bipolar global system in the global arena. Then, having failed to sus-tain the burden of being a superpower, the country lost critical leverage it had in the world, including NEA.

China, following a long period of revolutionary struggle and socio-political upheavals of the 1950-60s, has moved forward to join the ranks of the world’s leading powers and started to have an increasingly impor-tant influence on the situation in the NEA Region.

Japan, defeated in World War Two, found itself to be closely de-pendent on the United States. Nevertheless, having preserved its national identity and its unique historical and cultural characteristics, it has shown an amazing ability to use this dependency for adopting modern democ-ratic standards and values and has transformed itself into one of the ad-vanced, powerful and technologically and economically dynamic states of the world. Japan’s foreign policy influence, including in the NEA Region, has so far been lagging behind its economic power, which gives the coun-try an incentive to pursue a more active foreign policy and compete for influence in the Region.

Korea, following the defeat of the Kwantung army by the Soviet Army, was liberated from protracted colonial rule, but, after becoming one of the focal points of the confrontation between the great powers, it split into two states confronting one another. The inter-Korean armed conflict, directly involving the United States and China, and indirectly the Soviet Union, gave a long-term impetus to the deepening of that rift. Ko-rea became a victim of the Cold War in the East. Developments in the North and in the South proceeded along diverging lines, throwing into question the very existence of a united Korean nation.

In the wake of World War Two, the United States gained a strong foothold in the NEA Region, both in the politico-military and in the eco-nomic sense, gaining an opportunity to play a dominant role in the devel-opments in Northeast Asia.

The end of the Cold War and of the stand-off between the opposing alliances in the world arena once again radically changed the situation in NEA: Russia and China restored normal political and economic relations with the Republic of Korea; the two Korean states were admitted to the UN, the intensity of military confrontation was reduced, and contacts are developing between North and South Korea.

The situation in the world has become much more favorable for overcoming the division of the Korean Peninsula, which is last relic of the Cold War. However, it would be premature to assert that a steady trend towards stability has gained the upper hand there.

The Korean Peninsula still remains in the orbit of militarization, which includes an extremely dangerous nuclear weapons dimension. This is especially true of DPRK. Despite its grave financial and economic situation, there has been no reduction in DPRK’s military spending. The numerical strength of DPRK’s regular armed forces is more than double that of Viet Nam; more than three times that of Indonesia; seven times that of Cambodia; ten times that of Malaysia; seven times that of Thai-land; ten times that of the Philippines; almost two times that of South Ko-rea; and four times that of the Self-Defense Forces of Japan. Taking into account the combined strategic military capabilities of DPRK and the Re-public of Korea (given that, in absolute terms, the military budget of the ROK is several times greater than that of North Korea), the Korean Pen-insula today is one of the world’s most militarized areas.

The military and political situation in Northeast Asia in general and in the Korean Peninsula in particular is affected by the vast military capa-bilities of China and Russia and, of course, by the U.S. military presence in the subregion. More than 100,000 U.S. military personnel are deployed in South Korea and Japan (35,500 and 80,000 respectively). The with-drawal of 12,500 U.S. soldiers and officers from South Korea, carried out under the program of “redeployment” of the U.S. troops, is offset by the efforts aimed at modernizing their armaments and equipment.

Excessive militarization of the Korean Peninsula is also spurred by the politics of global military-industrial business, which opposes any pro-grams of conversion. Along with Taiwan, South Korea is the largest buyer of the U.S. weapons. Russian weapons are supplied to the Korean Peninsula. At the same time, deliveries of arms, particularly of missiles and missile technology, by North Korea to other countries are one of its main sources of foreign exchange.

Supermilitarization of the Korean Peninsula is generating chronic attitudes of armed confrontation in the region, something that Europe, for example has largely abandoned. Neighboring countries are watching the situation as regards nuclear weapons and missiles in the Korean Peninsula with great concern, as North Korean military technologies spread to Asian and African countries (Pakistan, Syria, Iran, and others). Japan is particularly worried, as it is located within the reach of North Korean missiles. With Beijing stepping up its military efforts, the ruling circles of Tokyo are reviewing Japan’s military doctrine with a view to removing the constitutional restrictions on the use of military force instituted fol-lowing the end of the World War.

The economic situation in NEA is also complex and contradictory. The Region’s countries are developing in the context of intensification of the processes of globalization. Some of these countries have demon-strated, to a greater or lesser extent, the well-known phenomenon of “the Asian miracle.” Japan was the first to do so, followed by the first echelon of “the young tigers” (South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Taiwan), and then by the second echelon countries (Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines). Over the span of the two decades of successful tech-nological and economic modernization, “the newly industrialized coun-tries” increased their national product by up to five times and gained a strong position in the global economy. The rapid economic expansion in China is opening up real prospects for it to usher in a new phase of “the Asian miracle.”

Pursuing their national interests, these countries have irrevocably joined the common flow of globalization, with all its challenges and dan-gers, shocks and benefits, as well as new incentives for growth. To gain a competitive edge internationally and penetrate the developed countries’ markets, they have adroitly used Western technologies and investments, while being equally successful in gearing to the needs of modern devel-opment their own social and cultural values and traditions, such as the unique work ethic, habitual observance of discipline, paternalism in the employer-employee relationships, community-corporate and family cus-toms and traditions, and even certain features of their religious mindset. “The newly industrialized countries” have given the world an object les-son in harmonious blending of the processes of globalization and local processes reflecting the needs of national development.

Globalization is an objective global process. However, it is now be-ing dictated by the most “advanced” states, which employ not only eco-nomic methods but also the powerful means of propaganda, PR and other mass media resources. For the United States – the main and only super-power – globalization serves as a means of consolidating a unipolar world system with U.S. hegemony. Following the 9/11 terrorist attack and the adoption by Washington of a new foreign policy doctrine, the policy of globalization has been carried out through pre-emptive use of force against “new threats,” above all the threat of international terrorism, with the United States showing its determination to rebuild the entire system of international relations in accordance with the patterns and priorities of U.S. “national security,” which often infringe upon the interests of other states and ignore their national characteristics.

While being part and parcel of the global process, the countries of Northeast Asia have succeeded in averting the threat to their traditional values. Their national culture, mindset, customs, morals, religious beliefs, and even ancient mythological perceptions – in short, everything that in a broader sense of the word shapes the inimitable character of “human rela-tions” typical of this society – has not “gone with the wind” of “the civili-zational aggression” blowing from the West. The countries of the Region have preserved their national identity.

“The era of the Asian miracle,” as seen at the end of the 20th cen-tury, is by all appearances nearing its end. The Western markets are over-stocked with cheap consumer goods made in China and in the newly in-dustrialized countries. And, most importantly, the world is increasingly plunging into a postindustrial stage of development, where formerly effi-cient technologies can no longer provide a competitive edge. To achieve this, one needs high science, continuous technological innovations, vast research potential and highly professional human resources. All this can only result from high educational standards among both workers and pro-fessionals and from an appropriate cultural environment.

In the 1990s, Japan became concerned that it was clearly lagging behind the United States and Europe in the production and exports of “in-tellectual goods.” In 2000, an ambitious Action Plan for the Creation, Protection and Use of Intellectual Property was announced, which imme-diately brought the spending on scientific research to the level of US.6 billion a year – four times the amount spent by the United King-dom and three times that of Germany.

Similar reorientation is taking place in China and South Korea. Starting from the mid-1990s, the share of investment earmarked for Re-search and Development has far exceeded that in the UK and France. The share of the GDP allocated to scientific research and higher education in the countries of Northeast Asia has increased two to three-fold. Malaysia has developed a plan for creating its own “Silicon Valley” (Multimedia Super Corridor).

By all indications, a new phase of the global integration is in the offing. It is opening up new opportunities for the NEA Region, though simultaneously it is revealing the problems resulting from the wide dif-ferences in the level of development of Region’s countries, in the extent to which they are involved in the integration processes. On the one side are the far-advanced Japan and South Korea; while on the other side we see North Korea, virtually isolated from the international processes; the Russian Far East, just recovering from a prolonged depression; and the underdeveloped Mongolia.

As for Russia, the problems of the Far East are a reflection of the general situation in the country. It is going through a period of transfor-mation, which influences the country’s overall economic and social situa-tion. It has enormous potential to participate in the processes of integra-tion. If it is true that, as predicted, the Pacific part of Asia will become the main focus of the global economic growth, then Russia has to be in a hurry if it is not to miss the train. The Far East and Eastern Siberia need to be developed at faster-than average rates, while strengthening, rather than weakening, their links with the European part of Russia.

Immediately after the liberation from Japanese rule, North Korea was significantly ahead of South Korea in terms of industrial and eco-nomic potential, while in the final third of the past century the North fell hopelessly behind the South. The one-sided emphasis on economic rela-tions with the Soviet Union brought the country into dire straits when in the early 1990s those relations went sour. Chinese assistance failed to off-set the resulting damage. However, an even more negative role was played by two other factors. The first one was the extremely rigid version of the command economy system developed in the country, which un-dermined incentives for work and entrepreneurial activities; the second one was the huge military expenditures consuming up to 30 percent of the gross product and up to 50 percent of the state budget. The living stan-dards of the population plunged in an unprecedented way and shortages of essential commodities, like foods, fuel, etc., became widespread. Lately, the situation has improved somewhat, but it still remains difficult.

The growing gap in the living standards in the North and in the South of Korea aggravates the problem of North Korean refugees and has a negative impact on DPRK’s relations with ROK and the PRC, where most of the refugees are headed. The North Korea Human Rights Act, approved by the U.S. Congress and signed by the President, which pro-vides for annual allocation of US million (i.e. a total of US mil-lion) during the period of 2005 through 2008 for payment of expenses re-lated to resettlement of North Korean refugees, has added fuel to the fire. This action, encouraging a growing flow of refugees, has raised a storm of indignation in Pyongyang.

Analysis of the current situation convincingly shows that prospects for the development of the NEA Region, both politically and economi-cally, are inseparably linked to ending the military and political stand-off between the two Korean states, to securing a non-nuclear status of the Korean Peninsula, and to progress on the way toward inter-Korean set-tlement and to peaceful democratic reunification of the Korean people.

Unification of the two Korean states could draw a final line under the Korean problem in its present form, i.e. remove the Korean Peninsula from the category of explosive regions of Northeastern Asia. However, this task is not on today’s or tomorrow’s agenda. In our view, it will take quite a long time, and it is therefore not on the agenda of practical poli-tics. To quote the President of the Republic of Korea, Mr. Roh Moo Hyun, “this is our dream.” However, its realization could be brought closer by giving it a realistic shape. To this end, focused efforts are needed on the part of both Korean states and on the part of the great pow-ers involved in the problems of the Region.

Expert analysis of the evolution of the situation in the Peninsula and a possible solution to the Korean problem was presented in our report Russia and Inter-Korean Relations (Gorbachev Foundation, Moscow, 2003). It contains a conclusion that “Russia, more than any other great power, is interested in the unification of Korea into a peaceful democratic state playing an independent role in the world arena.” The course of de-velopments that followed has fully confirmed this statement.

Russia’s foreign policy approach to the Korean problem is based on the following main principles:

- maintaining peace and stability, preventing growth of tensions and scaling down the military stand-off in the Peninsula;

- complete prohibition of the spread of weapons of mass destruc-tion, including nuclear weapons, in the region;

- a major effort to develop cooperation with the Republic of Korea as an important economic and political partner in NEA;

- developing ties with DPRK on a mutually beneficial basis, help-ing it to solve its severe social and economic problems;

- priority focus on trilateral Russia-DPRK-ROK economic coop-eration (with possible involvement of other countries) in addressing prob-lems in the areas of energy, natural resources, telecommunications, etc.;

- coordination of efforts aimed at addressing Korean issues with all parties to this process; facilitation of normalization of DPRK’s relations with the United States and Japan.

Russia’s Korea policy is, in our view, perceived favorably both by South Korea and, as regards a number of its aspects, by DPRK. It helps to create favorable international prerequisites for the settlement of the Ko-rean problem. The implementation of this policy in practice will require patient diplomacy, mutual understanding, and willingness to take con-crete steps to accommodate one another.

As for the relationship between the two Korean states, one could only welcome the development and implementation of a strategy of rap-prochement between the North and the South. In our view, it could in-clude:

- trade and economic, scientific-technical and cultural cooperation along the lines of gradual convergence and linkage of the processes of development of productive forces in the South and in the North;

- granting the Korean Peninsula a legal status of a zone free of WMD and their delivery vehicles;

- reduction of the armed forces and conventional armaments of the ROK and DPRK to levels of reasonable sufficiency;

- creation of a climate of political and public trust between the two parts of Korea, including phasing out of media wars;

- gradual opening-up of the two parts of the Korean Peninsula to normal humanitarian mutual exchanges, reunion of separated families and implementation of practical steps in the human rights area;

- creation of pan-Korean consultative institutions on the basis of parity in various spheres of public life and administrative governance;

- coordination of positions and initiatives on international issues with gradual expansion of the range of such issues.

Implementation of such a strategy would gradually create a basis for further progress on the way toward unity of the Korean people.

2. Prospects for Economic Integration in NEA and Russia-Korea Cooperation

Opportunities and prospects for NEA countries in developing re-gional economic ties are linked to the enormous resources of the subre-gion and to the disparities in terms of resource endowment among its countries. Its natural resources are concentrated in Siberia and in the Rus-sian Far East, in North-Eastern China and Mongolia, and in the ocean and sea zones adjacent to NEA. Japan and South Korea and, more recently, the People’s Republic of China, have vast capabilities in technology, fi-nance and investment. Russia, including Siberia and the Far East, still re-tains considerable scientific potential. Surplus labor is concentrated in China and in North Korea. Cooperation based on the combination of all these inputs and natural resources could serve as a firm foundation for economic growth and mutually beneficial cooperation between the coun-tries of the Region and for future economic integration in Northeast Asia.

The peculiar gravitational pull of the geographical space of the ba-sins of the Sea of Japan/East and South China Seas is also favorable for economic cooperation in the region.

After the consequences of the 1997 financial crisis were repaired, an overall improvement of economic conditions has been observed in NEA. China’s progress is particularly impressive, although many econo-mists note an overheating of the Chinese economy, the country’s enor-mous internal debt, and an excessive amount of bad loans. The policies of Central Bank of China, which is holding down the growth of the ex-change rate of the national currency, are adding to the discontent in the U.S. and other countries that are foreign trade partners of the PRC.

South Korea has successfully overcome the consequences of the fi-nancial crisis and achieved a healthy rate of growth. In 2004, GDP growth is estimated to grow 5 to 6 percent.

Following a long period of stagnation, an economic recovery has taken place in Japan, where GDP growth in 2004 will be more than 4 per-cent; the situation in the banking sector has improved and the government is beginning to address in earnest the issue of reform in the corporate and public sectors.

An economic recovery has continued in Russia. In 2004, GDP growth will be about 7 percent. Gold and foreign exchange reserves have approached the US0 billion mark. Accumulated foreign direct in-vestment in the Russian economy has reached the level of US billion.

The current foreign trade position of NEA countries is quite sub-stantial: they account for 15 percent of global exports and for 12 percent of the imports. However, these levels are primarily due to Japan, South Korea and China, which account for more than 90 percent of the exports by NEA countries and for almost 97 percent of their imports. The share of intraregional trade in the combined foreign trade of the six countries of NEA is 20 percent for exports and 25 percent for imports. The share of NEA countries in the foreign trade of Japan is 18 percent, while for the Republic of Korea this figure stands at 27 percent, and for China at 30 percent. The volume of intraregional trade is also primarily sustained by Japan, China, and the Republic of Korea.

Russia continues to increase trade and economic cooperation with its main partners in NEA: China, Japan, and the Republic of Korea. Rus-sia’s trade with China in 2004 will amount to about US billion, and with Japan to US billion. Stagnation in trade with ROK has been over-come. During their meeting in Moscow in September 2004, the Presidents of the Republic of Korea and the Russian Federation, Roh Moo Hyun and Vladimir Putin, noted the acceleration in the growth of trade between the two countries, with its volume in the period of January to September 2004 reaching US.3 billion. Agreements on cooperation in building a petrochemicals project in Tatarstan and modernizing the Khabarovsk oil refinery; a Memorandum of Understanding between Rosneft and the Ko-rean Oil Corporation on the development of oil reserves in Kamchatka and Sakhalin; and a loan agreement between the Vneshtorgbank (Foreign Trade Bank of the Russian Federation) and the ROK Export-Import Bank were signed during the visit of President Roh Moo Hyun.

Trade and economic ties between Russia and DPRK have remained depressed. Trade between them has dropped from US9 million in 2002 to US0 million in 2003 and to US2 million in the period of January to September 2004. Russia accounts for only 5 percent of foreign trade of DPRK, while the bulk of it is with the PRC, Japan, and the ROK. One of the reasons for that is DPRK’s refusal to settle the issue of its debt to Russia, even if through token repayments. This also explains the fact that DPRK has maintained trade and economic relations with Russia al-most entirely through agreements with its regions.

As to the overall assessment of the development of economic rela-tions and economic integration in the NEA Region, one must admit that it is far out of step with the opportunities that are available. Regional eco-nomic ties in Northeast Asia involve mostly Japan, China, and South Ko-rea, with Russia being represented to a far lesser extent. The largest coun-tries of Asia – Japan, China, and South Korea –hold a modest place in terms of direct investment in Russia and in its overall trade. North Korea and Mongolia remain part of NEA economic region in name only, mostly by virtue of their geographical location.

The development of integration processes in NEA is constrained by a number of factors inherited from the past. They include institutional dif-ferences between member-states, disparities in levels of economic devel-opment, and of course the still unresolved issues of security, DPRK’s nu-clear problem, outstanding border disputes and territorial claims. This does not mean that integration has to be put on hold pending the removal of these factors. In fact, progress on the way to deeper economic integra-tion in the region has a logic of its own and could facilitate improvement of the overall situation in the Region and resolution of other issues.

The development of integration processes in NEA and Russia’s in-volvement in them are to a large extent linked to prospects of the Russian Far East.

The idea of integrating the economy of the USSR with Asian Pa-cific and NEA countries was first formulated in the late 1950s by Acade-mician V.S. Nemchinov in the documents of the Productive Forces Re-search Council at the Gosplan (State Planning Committee) of the USSR. Its main point was that the natural resources of the Far East – timber, coal, furs, raw materials for ferrous and non-ferrous metals industries – cannot be efficiently utilized in the European part of the USSR, as on their way to the West they have to face competition from the less expen-sive similar raw materials produced in Siberia and in the Urals Region; however, resources of the Far East can become an effective basis for eco-nomic cooperation with the countries of the Pacific Rim. Starting in 1964, this concept was implemented in the form of compensation agreements with Japan on timber resources, coal, and natural gas. However, the full potential of this idea was not realized.

Under a new Eastern policy proclaimed by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Far East was to become the main testing ground for and conduit of Rus-sia’s economic, technological and intellectual role in the Asian Pacific Region.

However, up until now the idea of Russia’s involvement in the in-tegration processes in the Asian Pacific Region has been far from realiza-tion, even though it now looks more concrete. The main reason for that is the economic weakness of the Russian Far East, which has not yet be-come a significant and stable partner for the main actors in the economic system of the Asian Pacific region and NEA.

The Far Eastern Federal District territorially is one of the biggest in the Russian Federation, accounting for over 36 percent of its territory. Yet it accounts for slightly more than 4.5 percent of Russia’s population, 5 percent of industrial production, 3.4 percent of agricultural production, and 8.1 percent of the total investment made in Russia (data as of the end of 2003).

The economy of the Far East was hard hit by the crisis of the 1990s. Over the past 15 years, the region has ceased to be a major sup-plier of commodities for domestic and foreign markets, with the excep-tion of non-ferrous metals and fish products. This was due to the fact that locally produced goods have become less competitive due to the unfavor-able prices and transport rates fluctuations and due to cuts in state subsi-dies. The economic downturn gave way to a modest recovery in 1999; nevertheless, the Far East in terms of its development still lags behind the rest of the Russian economy (see Table 1).

Table 1. Volume of Industrial Output

(percentage points, as compared to the previous year)

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003

Russia 111.0 112.0 104.9 103.7 107.0

The Far East 107.0 107.0 99.9 99.1 104.7

In a number of industries, above all in the timber, woodworking and pulp and paper industries, in machine building (particularly in the military-industrial complex), in the iron and steel industry and in the con-struction materials sector, the situation remains unstable. The structure of production in the region has shifted towards a greater share of the primary (natural resources) sector. There has been little progress in the process of defense conversion, though there is still a considerable innovation poten-tial in the military production sphere.

There have been conflicting trends in foreign trade. Exports of raw materials and products of primary processing have grown, as have im-ports of consumer goods. At the same time, links between the Far East and other Russian regions have shrunk dramatically – to an extent that is far greater than the drop in the volume of production. While in the early 1990s, exports of goods to other regions of the country accounted for 75 percent of the region’s output, with goods exported abroad accounting for only 6 percent, by 2003 the share of exports to the Russian domestic mar-ket shrank to 4.3 percent, with the share of foreign exports growing to 18.2 percent. Foreign trade is thus supplanting economic exchanges with Russia’s other regions.

Northeast Asia, above all China, Japan and the Republic of Korea, is the main market for the Russian Far East. The share of these countries in the trade turnover of the Far East has consistently exceeded 50 percent, regardless of market fluctuations.

Table 2. Share of NEA Countries in the Trade Turnover of the Far East

(percentage points)

1992 1995 1998 2000 2003

NEA Countries, to-tal 80.3 51.6 60.5 56.5 69.2

including:

Japan 35.1 32.5 18.8 19.5 22.0

PRC 36.1 7.8 22.9 24.6 31.4

South Korea 9.1 11.3 18.8 12.4 15.8

By 2003, exports from the Russian Far East to NEA countries grew 2.3 times over 1992, with imports rising more than 40 percent. The main items of export to NEA in 2003 included: fish and fish products (23.7 percent); machinery, equipment and transport vehicles (21.6 percent); oil and gas (21.5 percent); timber and pulp and paper products (18.2 per-cent); and coal (5.9 percent).

For the Russian Far East, trade with NEA countries is highly im-portant. However, its share in the foreign trade of Japan, South Korea and China is paltry. Even lower is the volume of cooperation in the spheres of investment, science and technology, and joint production.

Russia’s political circles, academic community and the general public are aware of the fact that modernization of the economy and rais-ing the living standards of the population of the Far East require intense engagement of the region in the integration processes now under way in NEA. However, this awareness must be reinforced by political will on the part of the central government and focused on the acceleration of devel-opment of social and economic infrastructure and of links with Russia’s other regions, on improvement of the investment climate in the region, on building up the capacity for foreign economic ties, etc. Consolidation of “vertical power” (executive chain of command) in the country, intensifi-cation of the campaign against red tape and corruption, and revamping public administration and personnel could contribute to success in such efforts.

Integration of the Russian Far East into NEA is one of the top pri-orities of the Federal Target Program for the Development of the Far East and the Trans-Baikal Region up to 2010 (approved in 2002), which calls for reaching faster rates of development in the region compared to the rest of the country.

The growth of investment in the Region in 2001-2003 (44 percent) was significantly higher than the 26 percent projected in the Program. These investments go mainly to infrastructure development. But if they are to impact economic growth in the Region, “an institutional multiplier” is needed - otherwise, the already high level of capital intensity of pro-duction growth will become unsustainable.

The prospects for economic development of the Russian Far East are linked both to the consolidation of its role in the Russian economy and to its more intensive involvement in the integration processes under way in NEA, to implementation of a number of major projects in the area aimed at creating the economic infrastructure in the region, and to the shared use of its resources. In large part, these prospects depend on the level of cooperation between Russia and Korea.

An intercontinental bridge linking Southeast Asia and Europe through the territory of Russia is the largest project now being consid-ered. Reconnecting the Trans-Korean railroad and linking it with the Trans-Siberian railroad would be a starting point and a key component of this project.

An intercontinental railroad link would have clear economic advan-tages over the sea route crossing the Southern seas, along which more than 12 million freight containers (20 feet equivalent) are shipped annu-ally from Eastern Asia to Western Europe and back. Freight transit time would be reduced by a third, with the consequently lowering of the ship-ping costs. Attractiveness of the Southern sea route is negatively affected by the complicated political situation in the Middle East. Therefore, ma-jor Asian businesses are seriously concerned about the safety of shipping and are interested in alternative routes.

Reconnecting the Trans-Korean railroad and linking it to the Rus-sian Trans-Siberian railroad is not only an economic but a political matter as well. Success of this project depends on the status of relations between the two Korean states and could, in its turn, make a major positive impact on their relations.

One of the options for reconnecting the Trans-Korean railroad and linking it to the Transsib is “the Western Route,” going from Pusan via Seoul and Pyongyang to the Chinese Shenyang and further, with a link to the Transsib near Chita. “The Eastern Route” lies along the eastern coast of the Korean Peninsula from Pusan to the Rajin-Sonbong (DPRK) free economic zone, crossing the Russian border near Hasan, where it links with the Transsib.

Both options require fundamental improvement of the motor ways adjacent to the route and of the entire infrastructure in the Korean Penin-sula and, under the first option, also in China There is also a need to jointly develop agreements on transport tariffs, cargo insurance and trans-border railroad operations.

“The Western” variant of the transportation bridge linking NEA and Western Europe is less expensive and more competitive in terms of transit traffic. However, the “Eastern” option also has its strong points: fewer crossings of state borders and, consequently, fewer clearance for-malities, and additional possibilities to use the capacity of the transconti-nental bridge thanks to better utilization of the port capacity of the Rus-sian Far East.

The most important thing, however, is that “the Eastern Option” better fits the overall context of the processes of economic integration in Northeast Asia and development of vast natural resources of the Russian Far East. Modernization and development of the transport infrastructure of the subregion could give a major impetus to this process, benefiting not only Russia but all of the adjacent states as well.

In our view, attention should also be given to the broader interpre-tation given by a number of scholars to the idea of an intercontinental bridge linking the West and the East of Eurasia, envisaging comprehen-sive utilization of the territory of Russia, its air space and the Northern Sea Route to establish a modern communications system with a highly developed infrastructure on the Eurasian continent. Both the European states and the countries of NEA and of the entire Asian Pacific Region objectively have an interest in this project.

One of the most important spheres of cooperation between Russia, the two Korean states and others countries of the subregion is the devel-opment of energy resources of Siberia and the Far East and their transpor-tation to NEA countries.

A future system of international integration in the sphere of energy in NEA could be based on hydrocarbon resources of Eastern Siberia and the Far East: the Kovykta gas condensate field in the Irkutsk Region, the Chayanda oil and gas condensate field in Yakutia, and the offshore fields near the Island of Sakhalin. The Kovykta oil field alone has reserves that would make it possible, while fully meeting the needs of the Irkutsk and Chita Reguions and the Republic of Buryatia (about 10 billion cubic me-ters a year), to export up to 20 billion cubic meters annually. It is those resources that could provide the basis for the creation over the long-term of an engineering and transport infrastructure for international coopera-tion in the energy sector, including long-distance pipelines, liquefied natural gas production facilities, and power lines, covering the entire re-gion of NEA,

Various options are being considered for constructing oil and gas pipelines along the “West-East” routes from the Siberian and Yakutian oil and gas fields, and along the “East-East” routes from the Sakhalin oil and gas fields. In all, this would contribute to the creation in NEA of a com-petitive market of energy resources – an alternative to the current monop-oly of the Middle East in oil and gas supplies. With Australia joining the process, creation of a competitive energy market in Northeast Asia ap-pears quite realistic.

Prospects for Russian electric energy supplies to NEA also look promising. This is particularly important for DPRK. Power outages that started in North Korea in the late 1980s have by now turned into a major problem – one of the causes of the economic and humanitarian crisis in the country which poses a threat to security and stability in the entire NEA Region.

DPRK’s energy sector has long been neglected. Addressing the se-vere shortages of electricity requires modernization of the existing gener-ating facilities and power lines and creation of new ones, yet North Korea does not have the funds to invest in such programs.

At the Sixth Russia-Korea Forum in October 2004, the delegation of the RF presented concrete proposals as to the urgent measures to be taken to overhaul DPRK's energy sector. The proposals include comple-tion of the second stage of construction of the 1,000 mW East Pyongyang thermal power station (which would require the investment of US million) and retrofitting the 400 mW Pyongyang thermal power station (US0 million) and the 1,160 mW Pukchang thermal power station (US0 million). If financing is found to pay for supplies to DPRK of necessary equipment, the Russian side could implement these projects in cooperation with the Republic of Korea and international financial institu-tions.

Construction of a 500 kV power line linking the city of Vladi-vostok and the northern part of DPRK (the area of Chŏngju) could, ac-cording to experts, become a real contribution to the solution of DPRK's energy problem. The cost of construction, which would take three to four years, is estimated at approximately US0-180 million. The implemen-tation of this project would also allow for exports of Russian electricity to the Republic of Korea, if a high-voltage power line is extended to the border of the Republic of Korea.

As for the required financial resources, the following suggestion could be made. As of November 2004, the total humanitarian aid supplied to North Korea through the United Nations and the Republic of Korea channels since the mid-1990s amounted US.2 billion, including US5 million provided by the ROK. While this assistance has helped to alleviate the grave food shortages in DPRK, it has not addressed the urgent needs of modernizing the country’s economy, particularly the en-ergy sector. Meanwhile, investment from abroad amounting to just US billion (i.e. half the volume of the humanitarian aid) would spur signifi-cant overall recovery in DPRK's energy sector, industry and agriculture, and could thus result in a more meaningful solution to the food problem. As the saying goes, there are two ways to help a hungry man: give him a fish, or give him a fishing rod so that he could catch it himself. The latter option would appear preferable.

Another promising area of cooperation between Russia and NEA countries is the exploitation of forest resources of the Far East. The main partners of Russia in this sector are the two Korean states, Japan and China.

Russian exports to South Korea, China and Japan consist mostly of raw lumber and the country has virtually no share of the growing markets of such products as wood chipboards, plywood, wood paneling, etc. Only modernization of the entire forest industry, including logging and ad-vanced processing of timber, could change the situation for the better. The existing patterns whereby North Korea is granted logging areas in the Khabarovsk Territory and in the Amur Region, are outdated in terms of technology and logging management and from the standpoint of eco-nomic and social relations. What's needed to change the situation is for-eign capital, bringing with it modern technologies, management and labor force.

The issue of labor resources requires special attention. The bad demographic situation in the Russian Federation, particularly in its east-ern regions, poses a grave challenge to the country’s security. The popu-lation of the Far East declined from 8.1 million people in 1991 to 6.6 mil-lion in 2003. The availability of numerous vacancies, usually in low-paid and unattractive sectors, coupled with the surplus labor force in Northern China and North Korea, is pushing the Chinese and the North Koreans to seek employment opportunities in Russian territory. The problem is that migration here has developed along the lines that, to put it mildly, are far from modern or civilized.

237,000 Chinese citizens are officially registered in the Far East Region. However, in addition to them, there are many illegal labor mi-grants, the number of which is very hard to estimate. In fact, what is tak-ing place in the Far East is a spontaneous process of the emergence of Chinese Diaspora. The Chinese usually work “from dawn to dusk,” with-out taking days off, and are very undemanding in terms of living condi-tions. Russian employers take advantage of their habits of hard work and diligence and exploit their cheap labor.

Attraction of labor from DPRK to the neighboring regions of Rus-sia for employment in agriculture, logging and fish processing has been practiced for quite a long time.

Unlike the disorderly and spontaneous inflow of the Chinese, emi-gration of North Koreans is strictly controlled by their authorities. North Koreans are more disciplined than the Chinese. They do not seek work as salesmen in farmers' markets but work exactly in those enterprises to which they were sent. North Korean consulate officials have been known to levy a kind of tax on North Koreans working in the Far East of Russia to benefit their “starving fellow countrymen.” These funds were used to purchase food from China for the population of DPRK, to invest in pro-jects and enterprises in the Russian Far East, and to pay for Russian ex-ports to DPRK.

The scale and the modalities of attracting foreign labor and the le-gal and socio-economic status of the immigrants could change for the bet-ter if major economic projects are implemented in the territory of the Russian Far East, aimed at creating a Eurasian transportation bridge and bringing in foreign capital to develop Russia's natural resources.

Cooperation in the spheres of science and technology and innova-tion has played and will continue to play an increasing role in the proc-esses of integration.

In the NEA Region, South Korea and China are the countries with whom Russia has been able to cooperate rather successfully in this sphere. Under an agreement between the Korean Foundation of Science and Technology and the Russian Academy of Sciences, joint research is being conducted in more than 100 projects in areas such as laser tech-nologies, space exploration, biotechnologies and fiber optics and in de-veloping diamond substitute materials. The Far East Research Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences has been actively involved in these pro-jects. An agreement on cooperation in exploration and use of outer space for peaceful purposes, signed by the President of the ROK, Mr. Roh Moo Hyun, during his visit to Russia and on developing long-term guidelines for cooperation in the sphere of science and technology will undoubtedly provide a new impetus in this area of cooperation.

Scientific and technological cooperation with the PRC is gathering momentum. Cooperation in this area has also been resumed with DPRK.

Development of bilateral and multilateral innovative cooperation in NEA would be further facilitated by the creation of "testing grounds" that could serve as platforms for such efforts in free economic zones with spe-cial institutional arrangements.

While acknowledging the importance of infrastructural, energy and resource-based projects in the cooperation between the Russian Far East and NEA countries, it has to be recognized that in and of themselves they are insufficient for a radical breakthrough in the region's economic devel-opment. A major modernization of investment policies is needed, aimed at channeling revenues from the material exports to the creation in the southern part of the Far Eastern Region of major centers of sophisticated high technology production. Unfortunately, efforts in this direction have hit the wall of legal difficulties and the conservatism of government agencies.

Realization of the available opportunities to develop economic co-operation in NEA and promote the integration processes requires a broad systemic and strategic approach and establishment of multilateral mecha-nisms for interaction of participating countries.

The subregion does not any have interstate agencies like the Euro-pean Union in Europe or ASEAN in Southeast Asia. Development of in-tegration in NEA has been carried out through mutual penetration of other organizations of the Asian Pacific Region, such as the Asia-Pacific Eco-nomic Cooperation Forum (APEC), Association of South-East Asian Na-tions (ASEAN) and Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM). Plans are now being considered for the creation of East Asia Forum, with the participation of China, Japan and South Korea, and for involving China and Japan in the Free Trade Area of ASEAN countries (AFTA).

In practical terms, the rapprochement between NEA countries has been in the form of bilateral or trilateral agreements. For example, Japan and South Korea are working on an agreement to establish a free trade zone. China, Japan and the ROK have set up a trilateral think tank which is expected to submit to their governments agreed recommendations on coordination of economic and financial policies and the development of trilateral cooperation in trade and investment. In the academic and busi-ness communities, analysis has been started of major problems such as creation of a common energy circle in NEA, transportation corridors from the subregion to Europe through the territory of Russia and establishment of a free trade zone and monetary union in Northeast Asia.

The Japanese business community has initiated proposals for creat-ing “a free business area” in NEA. It is expected to integrate the econo-mies of China, Japan and South Korea, while not closing the doors to U.S. companies willing to participate in the projects to develop the natu-ral resources of Eastern Siberia and the Russian Far East and to use the Russian transit territory for links with the countries of Europe.

This will require harmonization of common legal regulations to provide guarantees of and protection for free movement of goods, finan-cial flows, labor and academic exchanges in the region. A common in-vestment regime has to take shape, including joint standards, a single sys-tem of financial audit, reciprocal lifting of visa requirements and changes in education and training systems. This calls for a multilateral negotiation process within the framework of a standing regional inter-country institu-tion. However, institutionalization of cooperation for integration in NEA is still in its infancy and has not moved off the ground at the inter-governmental level. Discussion of the issues of cooperation has been car-ried out largely within the framework of non-governmental organizations, like NEA Economic Forum, the Gas Forum, NEA Economic Conference, etc.

Search for sources of funding for subregional projects is a key component of the strategy of economic integration in NEA. According to the estimates made by the Institute of Far-Eastern Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, US.5 billion in investment is needed annually to create an infrastructure for integrational cooperation in NEA. US.5 bil-lion could be realistically attracted from member-states and existing in-ternational financial institutions.

Increasingly, the need is felt to establish a joint Bank for Develop-ment of NEA as a regional financial organization. This idea is promoted by members of the academic and business communities. According to their proposal, government agencies of the United States, Japan, South Korea, Russia and China could become shareholders in the Bank, which would attract financial resources from the world market for the needs of NEA. The Bank would borrow money on a long-term basis in the world's financial markets through issuance of bonds. The money raised in this way could then be loaned in the form of long-term credits for the devel-opment of infrastructure, particularly the implementation of transporta-tion and oil and gas projects. Within the first five years of operation, the Bank, according to estimates, could accumulate US billion.

NEA Transportation and Natural Resources Development Council could become another subregional institution addressing the problems of resource and transportation infrastructures for integration. It would coor-dinate its activities with NEA Development Bank. By a similar pattern, NEA Council on Subregional Science and Technology Policy and a Council for Management of Labor Resources and Migration Flows could be set up. Yet another subregional body is needed to ensure coordination of macroeconomic and financial policies of the Region’s countries.

In the longer run, all the above institutions could form the back-bone for shaping a comprehensive structure for integration – the East Asian Union (EAU).

The situation in NEA has so far been developing in such a way that Japan, China and South Korea are dealing more with the ASEAN Ten, i.e. with the already established economic community in Southeast Asia, and have shown less interest in strengthening their role in the develop-ment of integration in NEA. Yet, it may be assumed that, as political ob-stacles are removed and major economic projects are developed, the situation in the subregion and consequently attitudes of the countries will be changing.

As for Russia, it is important for it to participate in the Asian Pa-cific integration at every level: at the regional level within the framework of APEC, the interregional in the ASEM (Asia-Europe Meeting), bring-ing together the EU and the ten countries of Asia-Pacific, and the subre-gional, i.e. within the framework of NEA. These three levels are supple-mented by bilateral relations, including cooperation in border areas.

At the initial stages, Russia’s participation in NEA integration ini-tiatives could possibly take the form of “special customs territories.” This concept calls for granting some autonomy to the economy of the Russian Far East on issues of strategy, tariffs and monetary policies. This would help avoid possible conflicts that might arise in the implementation of Russia’s strategy of creating a common economic space with the Euro-pean Union on the one hand and its participation in a longer-range but ob-jectively inevitable process of shaping an economic community in NEA, on the other.

All the above is, of course, a general outline of ideas related to economic integration in NEA. For the process to enter a practical stage, the governments of the subregion’s leading countries will need to show political will.

3. Issues of Security and Political Cooperation in the Context of Solving the Korean Problem

For almost sixty years now, the problem of the Korean Peninsula has been in the foreground of world politics. However, the developments since October 2002, particularly their nuclear dimension, are the most se-vere and large-scale crisis since the Korean War. It carries a real threat of escalating into not just a local but wider military conflict.

Framework agreements between DPRK and the United States con-cluded in 1994 have been virtually disavowed. Pyongyang and Washing-ton have been engaged in a complex, multi-dimensional struggle over DPRK's nuclear program. Both sides have firmly set forth their positions and are trying to gain an advantage both in the course of the propaganda war and in the six-party talks launched in Beijing in August 2003.

The history of the North Korean nuclear problem, which is seri-ously complicating international relations in the Asia-Pacific region, is rooted in the period of the 1950-70s, when DPRK was viewed by Mos-cow as “an outpost of world socialism in East Asia.” It might be recalled that soon after the end of the Korean War, the USSR and DPRK signed a number of agreements related to this problem. We are referring to the Framework Agreement on Cooperation in Science and Technology (Feb-ruary 1955), which provided for major assistance to Pyongyang in state-of-the-art technologies; a special agreement under which the USSR was committed to assist North Korea in constructing a nuclear reactor, radio-chemical laboratory, a cobalt plant, a nuclear physics laboratory and other facilities as part of a peaceful nuclear program (September 1959); an agreement between the Academy of Sciences of the USSR and the Acad-emy of Sciences of DPRK, under which North Korean nuclear research-ers got an opportunity to receive training at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna (February 1969). The texts of those agreements have not been made public. However, selective publications and expert com-mentaries suggest that they contained no firm commitments by the North Korean side that would completely rule out the possibility of transform-ing a non-military nuclear program into a military one, and DPRK made no clear and unequivocal commitment to prevent export of military tech-nologies to the third countries. The North Korean side later took maxi-mum advantage of these legal flaws in carrying out its nuclear weapons policy.

In the late 1980s, the Soviet leadership began to show more realism and balance in its stand on the situation in the Korean Peninsula and in matters of defense cooperation with DPRK. Ideology as a factor in rela-tions with DPRK was receding and could no longer be an obstacle to es-tablishment of diplomatic relations with the Republic of Korea, agreed in San Francisco in June 1990 by Presidents Mikhail Gorbachev and Roh Tae Woo. The volume and nature of defense cooperation with PDRK was reduced due to the fact that the policies of DPRK were no longer affected by Moscow's influence, and any new military conflict between the two Koreas would pose a threat to security near the Far Eastern borders of the USSR.

This step was quite forward-looking, since nuclear weapons later became the main foreign policy trump card of Pyongyang in its interac-tions not just with the United States but with all the other countries of the Asia-Pacific Region.

Following the breakup of the USSR, the Russian leadership made a number of diplomatic miscalculations in NEA, resulting in curtailing of Russian-North Korean relations and in stagnation of interaction between Moscow and Seoul. Relations in the Moscow-Pyongyang-Seoul triangle gained a new impetus only following the summit meetings of Russian President Vladimir Putin with the leaders of DPRK and the ROK during the period of 2000-2004.

So what is the situation now? In our view, the nuclear crisis in the Korean Peninsula will, in the near term, continue in a low-intensity mode.

Most experts on Korea agree that the nuclear game started by North Korea is meant to ensure the survival of the current political re-gime. Still, there remain substantive differences in expert assessments of the real capabilities of DPRK in nuclear weapons development and the progress made thus far. A group of independent U.S. experts, which vis-ited Pyongyang in 2004, has concluded that the North Koreans do possess nuclear energy technology but have not yet developed nuclear weapons. According to other sources, Pyongyang has at least two military purpose nuclear programs – a plutonium-based and a uranium program. North Ko-rea is ready to discuss and seek a mutually acceptable solution only for the plutonium program. In general outline, the plutonium infrastructure of DPRK consists of the following:

1. A 5 mW and a 50 mW gas-graphite reactors in Yongbyon [Nyongbyon].

2. One 200 mW gas-graphite reactor under construction in Taechon.

According to experts, weapons-grade plutonium is produced in the first two reactors. In their view, DPRK has by now produced 7 to 20 kg of plutonium, which is enough for 5 to 6 warheads. However, this is just an estimate and as of today no sufficiently convincing evidence has been presented as to the exact amount of plutonium produced or of the exis-tence of warheads.

Information about uranium production in DPRK is extremely lim-ited and conflicting. According to U.S. intelligence agencies, the Paki-stani nuclear scientist Abdul Kadir Khan transferred to the North Koreans the materials and know-how of centrifuge uranium enrichment. The North Korean side has at all times, including during the six-party talks, flatly denied the existence of a uranium program and is refusing to dis-cuss this issue. The Americans consider the underground facility in Taechon and the Laser Institute of the Academy of Sciences of DPRK in Pyongyang to be the key elements of the infrastructure for the uranium enrichment program.

The protracted stagnation in the peaceful settlement in the Korean Peninsula is increasing the threat of a “chain reaction” of nuclear weap-ons proliferation across NEA. Japan could well become the next state af-ter North Korea to go nuclear. With 50 operating reactors, it ranks third in the world in nuclear energy production, second only to the United States and France, and is one of the largest owners of plutonium stockpiles in the world, having enough plutonium to make approximately 1,000 war-heads. Chinese experts have concluded that Japan with its high technol-ogy base is capable of launching mass production of nuclear weapons on short notice. It is well known that constitutional restrictions prevent Japan from having nuclear weapons. But they will surely be lifted if DPRK ob-tains a nuclear bomb. Taiwan can also take the path of developing nuclear weapons. Such are the potential threats that could result from the unre-solved nuclear problem of DPRK.

Development of DPRK nuclear programs is linked to expanding the country's capabilities in WMD delivery systems. Its missile industry is developing rapidly, which allows North Korea not only to expand its own military power but also to get substantial foreign exchange revenues from the export of missiles and missile technologies. Pyongyang is ex-porting ballistic missiles to Egypt, Syria, Yemen, Iran and some other countries. While foreign exchange income from North Korean missiles exports has markedly dropped since the introduction of the Proliferation Security Initiative by the United States, it is still quite significant.

Currently, according to foreign experts, the following modifica-tions of ballistic missiles are produced in DPRK:

Scud, with 300 km and 500 km range;

NoDong, with 800 km and 1,000-1,200 km range;

TaepoDong, with a range of up 2,500-3,000 km and of up to 5,000 km (in development stage).

In 1998, a test of TaepoDong-1 was conducted (failed, according to experts, and presented in North Korea as a launch of an Earth satellite). According to U.S. sources, DPRK currently has 170 to 200 NoDong class ballistic missiles and 650 to 800 Scud missiles. Up to 100 missiles of various modifications are produced in the country annually.

North Korea's arsenals of ballistic missiles and possibly of nuclear warheads pose a real threat to the neighboring states. Under the North Korean doctrine, the countries classified as hostile include the United States, Japan and South Korea. It follows that “a nuclear deterrence weapon” and its delivery vehicles are being developed primarily against those countries. The North Korean nuclear problem has become an inter-national one, similar to the task of persuading India and Pakistan, who al-ready have nuclear weapons, to join the Non-Proliferation Treaty regime.

The North Korean leadership, citing the lessons of the U.S. inva-sion in Iraq without the approval of the U.N. Security Council, has as-serted that unilateral renunciation of WMD would threaten DPRK's secu-rity and sovereignty. Pyongyang has expressed readiness to freeze its military (plutonium-based) nuclear program if the United States provides security guarantees for North Korea and grants it economic assistance while Washington is insisting on the so-called CVID principle – com-plete, verifiable and irreversible dismantling of the North Korean nuclear program without any preconditions. In addition, the Americans are de-manding that Pyongyang end its uranium enrichment program as well as all its nuclear activities, including for peaceful purposes. North Korea has flatly rejected U.S. demands, stating that DPRK does not have a uranium program. The North Koreans have no intention of giving up construction of nuclear power plants.

The latest third round of the six-party talks (attended by the Rus-sian Federation, the People's Republic of China, the Republic of Korea, DPRK, the United States and Japan) on the settlement of the nuclear cri-sis in the Korean Peninsula, held in June 2004, like the previous two ses-sions, did not yield any concrete substantive results. Nevertheless, the talks that took place did have a certain positive element. They did not fol-low the scenario of creating a kind of five-party “alliance” against DPRK. All the participants in the dialogue, including DPRK and the U.S., agree that the Korean Peninsula should be free of nuclear weapons and that a peaceful settlement should be found to the current crisis.

The combination of international factors, including inter-Korean relations, suggests the possibility of progress in solving the North Korean nuclear problem in the foreseeable future. One factor conducive to such an outcome is the international community's commitment to seek a solu-tion within the framework of the six-party negotiating process. The latest G-8 Summit at Sea Island gave “firm support” to the Beijing talks and called on DPRK to suspend its nuclear programs. At the G-8 meeting Russia reiterated its view that the DPRK nuclear problem should be solved through negotiations. It also stressed that while the concerns of the international community must be addressed the interests of DPRK should be also taken into account. A scenario that must not be allowed to repeat itself is for DPRK to be left with nothing, as was the case in its relations with the Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO).

The People’s Republic of China has been playing a constructive role in the efforts to end the deadlock in the nuclear crisis on the Korean Peninsula. China used the visit of Kim Jong Il to Beijing in April 2004 to try to convince the leader of DPRK to adopt a more flexible approach to the resolution of the nuclear issue. It may be premature to say that Beijing has fully succeeded: North Korea has been playing its own game and does not appear willing to hand over the decisive role in the settlement of the nuclear problem to China, thus denying itself a chance for a direct discussion with the United States.

DPRK and Japan have stepped up efforts to normalize bilateral re-lations. Although the main theme of Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi’s second visit to North Korea in May 2004 was the issue of the abducted Japanese nationals, the subject of the nuclear weapons problem was also given attention. The leader of DPRK stressed that his country still in-tended to solve the nuclear issue through six-party negotiations and reaf-firmed the moratorium on ballistic missiles tests.

There have been positive developments in inter-Korean relations. Today it can be stated that the North and the South, despite the existing difficulties in solving the nuclear problem, maintain contacts and conduct economic negotiations. Despite some difficulties, the implementation of the Geumgangsan tourist project has continued, and the Kaesong project is entering a practical stage. Trade between the two Koreas has continued to develop. Another positive development has been the start of talks on military issues. A mutual decision by the North and the South to phase out the propaganda war and eliminate the technical means of special propaganda in the demilitarized zone was a landmark event.

The authors of this Report believe that in the current circum-stances, particularly given Washington’s intransigence and lack of flexi-bility on the part of Pyongyang, it would be appropriate to increase the significance of the inter-Korean dialogue, to be pursued alongside the multilateral talks. The two Koreas, who have shown clear willingness to be mutually forthcoming, could jointly develop an interim transition plat-form as part of efforts to move the Korean Peninsula toward a non-nuclear status on the basis of NPT principles. Such a platform could, for example, include a temporary freeze on nuclear research in the North of Korea in exchange for economic assistance. The platform would help to bring closer the two sides’ positions on the issue of nuclear disarmament of DPRK and facilitate the urgently needed process of demilitarization and, in the longer term, of conversion to peaceful purposes throughout the Korean Peninsula. Finally, it would be very important to revive humani-tarian exchanges between the two parts of Korea, which would offset, at least to some extent, the impact of the U.S. Congress resolution on finan-cial assistance to North Korean refugees.

All these would improve the political climate for the second sum-mit between the leaders of DPRK and the ROK, which would, in our view, be highly appropriate at the present stage, when the situation over the DPRK nuclear problem remains uncertain and the possibility of a new cycle of tension in the Peninsula is still there. The acknowledgement of secret nuclear experiments conducted in South Korea in 1982 and 2000 has contributed to the tensions.

The Report’s authors believe that there is a realistic possibility to solve the North Korean nuclear problem within the framework of six-party negotiations. In general outline, the eventual agreement between the Six would contain two main points: denuclearization of the Peninsula with security guarantees for DPRK and economic assistance to Pyongy-ang; in other words, “a freeze in exchange for compensation” as the first important step towards a non-nuclear status for the Peninsula. Of course the freeze should be internationally monitored.

In the course of further negotiations among the Six the following important decisions of a practical nature could be taken:

a) complete, verifiable monitored renunciation by DPRK of all its military nuclear programs;

b) granting by the United States of written legally binding guaran-tees of DPRK security, endorsed by other participants in the six-party talks;

c) return of DPRK to the NPT regime;

c) restoration of relations between DPRK and the International Atomic Energy Agency;

d) international assistance to DPRK in the energy sphere; restart-ing of the construction in DPRK of a nuclear power plant with light water reactors.

Endorsement of such a stand by all members of the Six would mark a real shift to the path of peaceful resolution of the nuclear crisis in the Korean Peninsula. If Washington officially confirmed that it gave up the intention of “removing” the DPRK “dictatorial regime,” prospects for po-litical settlement of the nuclear crisis would look quite realistic. In other words, a great deal depends on the political will of the leaders of DPRK and the United States and on their willingness to seek a solution to the conflict through mutual concessions and not to push the situation to the brink of an open military confrontation.

The practice of previous negotiations suggests that they will be long, hard slog, including protracted pauses and periods of marking time and even backsliding. This, however, should not discourage the parties.

In our view, with some constructive political will, it would not even require a major diplomatic effort for Washington to obtain a com-plete dismantling of the North Korean nuclear program in exchange for a step-by-step scenario of granting economic assistance to DPRK. Yet, the current U.S. stand shows barely any sign of a desire to resolve the crisis. Such a stand is bound to cause the apprehension that the U.S. Administra-tion is taking advantage of the prolonged tensions in the Korean Penin-sula to maintain and consolidate its positions in Northeast Asia. The near future will show whether such apprehension is justified.

It is the view of the Report’s authors that the six-party mechanism in the negotiations on the North Korean nuclear problem, even though it has not yielded major results thus far, could become a crucial element in a comprehensive set of arrangements to ensure security and stability in NEA. The six-party negotiating format is the most appropriate framework for a broader dialogue between all parties concerned.

A major advantage of such a dialogue is that it brings together three of the current five permanent members of the UN Security Council - the United States, China, and Russia - as well as Japan, а major player in international arena. The Four, together with the two Korean states, could arrive at decisions which would meet the interests of both Koreas, the Region, and the entire international community. In this process, it essen-tial that each of the six parties to the dialogue, above all Washington and Pyongyang, should refrain from unfriendly statements, threats, or other counterproductive actions.

Settlement of the North Korean nuclear weapons problem would open up new prospects for shaping a multilateral structure for security and cooperation in NEA.

It is a well-known fact that Northeast Asia does not have any insti-tutions for maintaining strategic security, except for the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF). The existing “vacuum” has prompted some Western ana-lysts, such as Zbigniew Brzezinski, to suggest transforming the Organiza-tion for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) into a Eurasian or-ganization extending its mandate to the Indian subcontinent and further to Central Asia, the Caucasus, China, the Korean Peninsula, South East Asia and the Japanese Islands. This concept of veiled hegemonism over Asia is rejected by China and other NEA countries. If positive results are achieved in solving the North Korean nuclear problem, the mechanism of cooperation in the six-party format could serve in the future as a founda-tion for building an East Asian model of organization for security and co-operation.

There are, of course, numerous major obstacles standing in the way of implementing this idea. In addition to the Korean problem, there are territorial disputes both in NEA itself and in the adjacent areas, above all the issue of Taiwan. Some individual countries of the region do not even have diplomatic relations (United States-DPRK and Japan-DPRK) be-tween them. The situation here in terms of regional cooperation is cer-tainly more complex and entangled than, say, in Europe, Latin America or Southeast Asia. However, this is yet another argument for making ad-ditional efforts in that direction.

In addition to achieving a non-nuclear status for Korea, the prob-lem of conventional arms reduction and demilitarization of the region re-quires attention and concerted efforts, as discussed in Section One of the Report. Development of clear-cut mechanisms of interaction between NEA countries could contribute to further improvement of international prerequisites for the settlement of the Korean problem. It might be re-called that thus far only the agreement on ceasefire in Korea is in effect, while the multilateral mechanism to monitor its observance is, for all practical purposes, not functioning. The six-party format could allow for discussion and development of measures to maintain environmental secu-rity in the region, to coordinate efforts to deal with natural and techno-logical disasters, etc.

NEA has vast potential for interstate cooperation in the fuel and energy complex and transportation, as discussed in Section Two of the Report. Attention should be given to exploring the issue of creating an Emergency Fund for International Assistance to North Korea - a kind of Korean version of the postwar Marshall Plan to rebuild Western Europe. The Russian side could participate in this initiative through supplies of equipment against financial guarantees of reconstruction of major na-tional economy projects previously built by the USSR in DPRK. The ROK could contribute to the Fund through assistance from major private corporations, particularly those that are already doing business in the North. Japan, China and other states of the Asia Pacific region would be likely to join the Fund. A special report presented by the Japanese expert Satoshi Saito at the Second Russia-Japan Scientific Practical Conference, held in September 2004 to discuss the prospects for providing urgent en-ergy assistance to DPRK, was notable in this respect. According to the Japanese expert, the question of providing assistance to North Korea should take center stage in the six-party negotiations, with Russia and the United States taking the lead. The Fund could undertake to partially fi-nance operations related to linking the railroads of RF, DPRK and ROK, which, according to preliminary estimates, would benefit all freight carri-ers of NEA and bring in huge commercial profits.

Establishment of such a fund would demonstrate the willingness of the world community to encourage Pyongyang’s steps towards market re-forms.

Multilateral forms of cooperation in NEA are by no means incom-patible with bilateral and trilateral formats or with the participation of the region’s countries in other international alliances extending beyond Northeast Asia, such as ASEAN, ARF, etc. In fact, they should mutually supplement and balance each other. One of the dominant characteristics of the situation in NEA on the threshold of the 21st century is the exis-tence of an array of bilateral, trilateral and multilateral interstate political mechanisms for dialogue: United States-Japan, Russia-China, United States-Japan-ROK, China-DPRK and China-ROK, Russia-ROK and Rus-sia-DPRK, and ROK-DPRK. The United States-DPRK and Japan-DPRK are the links that are missing.